Learn about Cornwall's dolphins and porpoises

Cornwall is among the best places in the UK to see these remarkable and charismatic creatures, and is home to one of the few resident pods of bottlenose dolphins left off the British Isles. Yet their populations remain fragile and the impact of human behaviour risks them being lost from our waters.

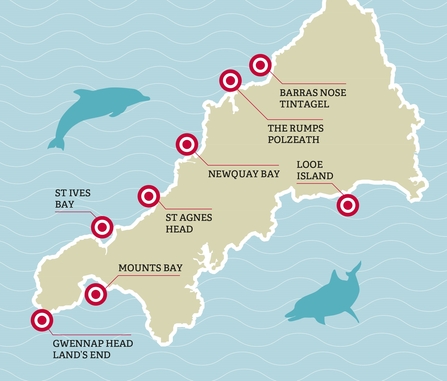

Where to see dolphins and porpoises in Cornwall

Cornwall is among the best places to see dolphins and porpoises. The locations on the map below are among the most likely places to see these wonderful creatures from a safe distance from the clifftops.

Species to look out for

There are lots of different species of dolphin, and just one species of porpoise that can be seen off the Cornish coastline, some rarer than others.

Harbour Porpoise

Harbour porpoises are small and stocky, with a dark grey back and lighter underbelly. Despite being a little shy and hard to spot, these amazing marine mammals can be seen close to our shores in shallow water. If you do manage to get close enough, you may hear their loud ‘chuff’ noise as they come to the surface for air, giving them their nickname ‘puffing pig’.

Common dolphin and calf, Image by Adrian Langdon

Common Dolphin

Common dolphins are seen around the Cornish coast all year round and have a beautiful hourglass pattern on their sides which make them easily identifiable. They are possibly the fastest dolphin on earth, capable of reaching speeds of up to 30 miles per hour. At sea, these energetic dolphins can form superpods – huge groups made up of thousands of individuals!

Risso's Dolphin by Niki Clear

Risso’s Dolphin

Sometimes called ‘gray dolphins’, these mysterious creatures are usually only found in deep offshore waters and hang out in pods of between 10 and 30. Risso's dolphins are easily recognisable by their large, domed heads, white colourings and highly scareed skin - a result of playing and fighting between individuals and catching prey.

Bottlenose Dolphin in St Ives Bay, Image by Dan Murphy

Bottlenose Dolphin

The South West is home to a resident pod of 28 bottlenose dolphins, believed to be the only resident pod of this species in England. It can easily be recognised by its short stubby beak and large sickle-shaped dorsal fin as the trailing edge is particularly susceptible to scratches and tears. This tissue rarely regenerates leaving permanent notches and markings which can be used to identify individuals much like our own fingerprints.

The South West Bottlenose Dolphin Project

The South West Bottlenose Dolphin Consortium, a partnership of stakeholders led by the Cornwall Wildlife Trust, was set up in 2016 to gather the information needed for their protection. Since then, the consortium has collated records and photos of bottlenose dolphin encounters, with reports coming from ferries, marine tour operators, charitable organisations, land-based observers and other interested parties. Sadly, this pod is in serious threat of decline due to their low numbers, lack of statutory protection and increased vulnerability to disturbance.

The threats to dolphin and porpoise populations

In Cornwall, we are incredibly lucky to have dolphins and porpoises off our shores. Yet they both face numerous threats, and unless we protect them, they could be lost from our waters. Three of the biggest threats to their survival are because of human behaviours.

On the 14th August 2020, a baby common dolphin stranded in Gunwalloe on the Lizard peninsula and was recorded by Marine Strandings Network (MSN) volunteers. A subsequent post-mortem of the dolphin was carried out and determined that the cause of death was head trauma, most likely caused by boat strike. The death came during a period in which the Cornwall Marine and Coastal Code Group (a partnership of organisations tackling the issue of marine wildlife disturbance which includes the Trust) was receiving extremely high levels of disturbance reports from the public.

This baby dolphin represents the very reason we are working so hard in Cornwall to raise people’s awareness of the issue of marine wildlife disturbance by water users. It is a devastating result which could have been avoided with more responsible behaviour.

Dolphin and porpoise strandings during 2021

Common dolphin - 91 (20 probable by catch)

Harbour porpoise – 22 (3 probable by catch)

Striped dolphin – 3

Risso’s dolphin – 2

Other dolphin species – 27 (2 probable by catch)

Total confirmed dolphin and porpoise strandings: 145 (including 25 probable by catch)

Disturbance

Disturbance, likely to be exceptional this summer due to high levels of domestic tourism, has been identified as a major issue. Cornwall Marine and Coastal Code Group data shows a significant increase in disturbance incidents in recent years, while University of Plymouth research indicates it’s the biggest threat to Cornwall’s bottlenose dolphins. Disturbance causes distress and affects behaviours including breathing, resting, feeding, breeding, nursing and migration. Direct impact with boats or other sea users can cause serious injury and at worse, death.

Bycatch

Cornwall’s fishing industry poses further threats. 27% of dolphin and porpoise strandings in Cornwall in 2019 were likely to have died following being caught accidentally in fishing nets (known as bycatch). The level of suffering for individuals who become entangled in fishing gear has been described as ‘one of the grossest abuses of wild animal sensibility in the modern world’. The victims of bycatch don’t drown, as they don’t inhale water. They instead close their blowholes and asphyxiate.

Noise Pollution

Developments along Cornwall’s coast have the potential to create a huge amount of noise underwater. Dolphins and porpoises have highly developed hearing and this noise pollution has serious implications on their wellbeing and ability to survive. It can cause disorientation and alarm, forcing them to flee feeding grounds. This can result in them not accessing enough food, causing malnutrition and (in the most extreme (but all too common) circumstances, starvation (the number of dolphin and porpoise deaths caused by starvation is sadly increasing). In addition, noise pollution can force dolphins and porpoises to rise from deeper water too quicky, causing ‘gas bubble disease’ (similar to the bends experienced by divers if they rise too quickly to the surface).

What we do to help protect dolphins and porpoises

Because the major threats to dolphins and porpoises are due to human behaviours, it means that with a focussed effort, working in collaboration and engaging coastal communities, we are able to do all we can to help.

Encourage sustainable management of our fisheries

Fisheries must be well managed to be both productive as well as environmentally sustainable. With Cornwall Good Seafood Guide we enable people to make good seafood choices by highlighting the most sustainable options from Cornwall’s 60 different species and 13 fishing methods. Working with the fishing industry and buyers of seafood, more sustainable behaviours leads to healthier seas and less bycatch.

To alleviate the problem of dolphin and porpoise bycatch, research has been undertaken by Cornwall Wildlife Trust and the University of Exeter which showed that underwater sound devices called “pingers” could be an effective, long-term way to prevent porpoises getting caught in fishing nets. The study of harbour porpoises off Cornwall found they were 37% less likely to be found close to an active pinger, with no negative behavioural effects.

Research and record marine populations

Utilising marine wildlife recordings and conducting research allows us to understand dolphin and porpoise distribution, diet, health, behaviour and ecology and assess the impacts of human behaviour. The Marine Strandings Network has been recording and monitoring dead marine wildlife strandings in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly for over 25 years. By studying dead marine life, we can begin to understand the actions required to best protect cetacean populations in our waters.

Seaquest Southwest project is a citizen science marine recording project which sets up events and surveys for volunteers to record their sightings which can then be used to give evidenced insight into the state of cetacean populations.

Influence national marine policy

Our marine conservation work focusing on dolphins and porpoises is recognised on a local, regional and national scale.

Our Marine Strandings Network is an official partner of the Defra funded Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP), coordinated by the Institute of Zoology. Members of the Trust’s marine conservation team represent our work at various working groups, such as Clean Catch UK - a collaborative partnership that brings together Government, statutory advisors, scientists and fishermen, to monitor and help reduce the accidental capture of wildlife by commercial fishing vessels.

Dr. Nick Tregenza, the former Secretary of the European Cetacean Society and an internationally respected cetacean researcher, is also the current President of Cornwall Wildlife Trust. For many years his work has focused on developing cetacean acoustic monitoring technology and testing bycatch mitigation techniques. His acoustic monitoring devices (C-PODs) are now being used around the globe to assess cetacean distribution and to study cetacean behaviour. We also sit on the Cornwall Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority where we have a voice in helping develop local fisheries management measures and byelaws.

Work with partners

Core to Cornwall Wildlife Trust’s effectiveness is our collaboration with partner organisations. Working together and drawing on each other’s strengths allows us to be as effective as possible for protecting marine wildlife. For example, we host the Marine Strandings Network which is set up to record and research dead marine mammals but work closely with British Divers Marine Life Rescue who focus on call outs to facilitate rescue and release of live cetaceans, and the Cornwall Seal Group Research Trust who monitor and record live seals.

We regularly join forces with partner organisations to develop campaigns and working groups. Cornwall’s Marine and Coastal Code Group, for example, is formed of 12 organisations who develop best practice guidance to enable individuals make recreational use of our seas and coast without disturbing wildlife.

Cornwall Wildlife Trust is only as effective as the individuals that support it. Those that volunteer, run local marine groups, attend trainings and are respectful when on or near the water mean that together, we can affect real changes. By supporting local and regional campaigns, setting up projects and supporting local marine groups, Cornwall Wildlife Trust can speak up on behalf of dolphins and porpoises, confident that we have your backing.

Can you help us do more of what we do best?

We need your help to continue this work – by making a donation to Cornwall's Dolphin and Porpoise appeal, give dolphins and porpoises a chance to not only survive but thrive.

Donate to the Dolphin and Porpoise Appeal

Inspired to take action?

You may think that the actions that you alone take won’t make a difference to the lives of our dolphins and porpoises. It’s often easier to think that changes made at council and government levels are the only the way to help these intelligent and social animals but that’s simply not true.

No matter where you live in Cornwall, whether on the coast or inland, you can do your bit to help marine wildlife and ensure we learn more about Cornwall’s dolphins and porpoises.

Wildlife conservation and the fishing industry

Recent media attention on the fishing industry has prompted many to consider the impact of their seafood choices. Documentaries such as Cornwall: This Fishing Life highlight the challenges faced by local fishers in a changing industry while films such as Seaspiracy challenge the misuse of terms such as 'sustainable' and call for radical action. Below you can read Cornwall Wildlife Trust's response to recent questions surrounding the impact of fishing and how this fits with wildlife conservation.

At Cornwall Wildlife Trust, what do we consider as sustainable fishing?

Sustainable fishing is a term used to describe fishing that is well managed and has minimal impact on the environment and other marine species that are not being targeted.

Unfortunately, it is a word that is often misused. Marine ecosystems are incredibly productive and when healthy they are one of the most efficient ways to obtain protein to feed humans. It is easy to get fishing wrong, however if too many fish are removed or if an ecosystem is damaged the system becomes vastly less efficient.

The Cornwall Good Seafood Guide rates all seafood caught and farmed in Cornish waters on sustainability using a rigorous system created by the Marine Conservation Society’s Good Fish Guide. This internationally recognised system uses up to date information from trusted scientific sources to calculate the status of the stock (population) of a fish species, the level of fishing pressure on this stock, how well the fishery is managed, and the wider impacts of the method being used to capture the fish (for example, seabed impact, accidental bycatch of non-target species such as dolphins, seals and sharks). Using this system we produce a list of seafood recommended by the Cornwall Good Seafood Guide. We do not run a certification system, but we provide up to date information to help us all make good seafood choices, and prior to the existence of this system there was very little information in the public domain about Cornish fishing – a complex and diverse subject, with over 60 species being targeted and 13 different fishing methods in use.

What are our views on what is widely considered sustainable fishing.

All methods of fishing have pros and cons. There is a big difference in the impact of large-scale industrial fishing such as pelagic trawling and the smaller-scale fishing carried out by Cornish day boats using a wide array of different methods of catching seafood. Fishermen are constantly trying to improve the way they work to minimise impacts, but there is always an impact of some kind.

For some people any impact is too much and we respect that viewpoint. However, we feel that there are huge gains to be made in ocean conservation by working with the fishing industry and the government to help create effective improvements. These improvements include measures such as: spatial management where some areas of seabed are rested and allowed to recover, gear modification to reduce impact (a great example being the use of acoustic dolphin deterrents, known as pingers, that alert cetaceans of nets) and regulations that restrict fishing for the long term benefit of fishers who in time will benefit from ocean recovery and healthier stocks. It is undoubtedly difficult to achieve truly sustainable fishing, however we feel that we are most likely to be able to positively influence the fishing industry to minimise its impact by working with the industry and informing consumer choice, rather than criticising.

Fishing is vital for Cornwall’s economy and culture, but as a wildlife conservation charity, we strive to protect nature and aid its recovery. As such, we believe that the best way we can reduce the impacts fishing has on our local seas is to continue our current approach of educating people - consumers, fishers, chefs and fish sellers - about sustainability and to continue to lobby for better management of our fishing industry to ensure long-term viability and minimal impacts.

Should we stop eating fish?

Many people can (and have already taken action to) stop eating fish and we completely respect that decision. No one with an environmentally-aware conscience wants to buy fish that supports fishing practices that damage our marine ecosystems. It is not realistic, however, to think that everyone globally will stop eating fish and that this is a solution to all fisheries issues.

In the UK, 97% of households regularly eat fish. Even if all of Cornwall Wildlife Trust's members stopped eating fish today the fishing industry would continue. Fish would continue to be exported and fishermen who have invested huge amounts of hard work and money into their boats and gear won’t stop fishing. Rather than campaign against fishing and engaging in polarising arguments, we think that by highlighting the most sustainable options (small-scale inshore fishing using hook and line or pots, for example) we can ensure that consumers are given the information needed to support good local fishing practices. By highlighting areas where improvement is needed we can incentivise government to better manage fishing. Instead of creating a divisive campaign calling on people to stop eating seafood, we call on our supporters to help us to use our collective power to call on industry and our government to manage our oceans properly.

Our oceans deserve it, but we are fully aware that a huge amount of work is still needed.